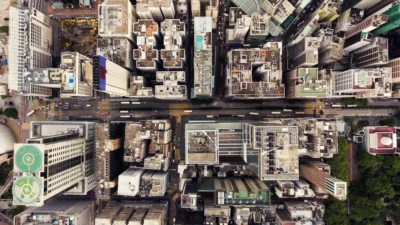

Meet the architect rethinking disability in urban spaces and how cities can be reimagined

Author David Gissen wants to move conversations about disability in the context of urban development beyond improving accessibility

David Gissen is a professor of architecture and urban history at the Parsons School of Design in New York City, whose latest book, The Architecture of Disability, makes the case that merely improving accessibility should not be the sole focus of disability representation and activism regarding development.

Rather, he says, disabled people can offer unique and valuable perspectives that could help architects and designers “reimagine what a house might be today—or reimagine what city streets, public infrastructure, or parks might be.”

“These are conversations in which disabled people have something exciting to contribute, while also going beyond some of the more paternalistic ways in which we have traditionally related to issues around disabled people,” Gissen adds.

The book has found a particularly receptive audience in the post-pandemic world, which has experienced a sharp rise in the number of people who identify as disabled.

Gissen says the positive response has come not only from architects and architecture students but also from real estate developers, urban planners, city leaders, and others who see broader potential for applying the ideas as global populations rapidly age and people with various disabilities continue to engage more fully in everyday life.

At the Asia Real Estate Summit, you presented virtually on “one-story cities”. Could you explain what this idea is about?

One thing that interests me a lot as somebody who has used a wheelchair in the past and now walks on artificial legs is efforts to bring the city down, so to speak, in terms of its scale and the number of stories that one experiences.

I know that sounds counterintuitive because we imagine that modern cities are ones where buildings get taller and taller. But going back 100 years, some people imagined that one quality of a modern city might be that it is lower.

There have been different visions for cities over the decades. After World War I, there was a population in Europe with an enormous number of wounded war veterans, and there were incredibly dense urban plans designed around one-story living and the same thing after World War II, also in Europe.

I often look at Asia for examples of dense one-story or low urban plans or developments. All kinds of precedents can inform how we want to build today

Vienna, Austria in particular had a very active organisation of disabled veterans. They remade the city in many ways that still can be felt today. Now, it’s considered a haven for disabled Europeans. It’s the only European capital city with a 100 percent accessible transit system. One of the things that was most interesting was they said: How can we remake public space around the needs of disabled people? A lot of people were so badly injured in the war that they had difficulty getting any type of employment.

They also wondered: What if we apportion a certain amount of public space for growing food? And that way, we ensure that people can eat. That idea is fascinating to me, and there are a lot of urban landscape architects and environmentalists in New York City and elsewhere today who ask whether our parks could become places to grow food or teach people gardening. I think that’s an amazing idea.

Are there other examples of one-story cities?

There are neighbourhoods in New York City today where most of the building stock—not the vast majority, let’s say about 50 to 60 percent—is only one story. These are neighbourhoods, about eight or nine square blocks in parts of Queens and Brooklyn, where one can live out one’s daily life on one floor, and that includes commercial spaces, of course, but also workspaces and even residential buildings.

When my students and I look at examples of very dense one story or low urban plans or developments, we often look at Asian examples. For instance, the hutong neighbourhoods in Beijing have some marvelous one-story multifamily dwellings. And there are similar areas in Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia, some really interesting examples. Japan, of course, the historic city of Edo.

So, there are all kinds of precedents for these ideas that can be thought about today in terms of how we want to build. I’d love to work or collaborate more with developers or others in Asia who are interested in these topics and to have some kind of cross-city exchange.

In The Architecture of Disability, you push back against the idea that access is the paramount issue with disability and development. Could you talk a bit more about your philosophy on this?

Accessibility is a very important part of disability politics when it comes to reimagining the built environment around disabled people’s needs. I don’t want to question the importance of that. However, I think it has tended to overdo the way that disabled people might reimagine the space around them and reimagine cities or the interiors of buildings or the infrastructure of cities.

In the chapter of my book on cities, I argue that disabled people might want to make alliances with people they wouldn’t think they have anything in common with. Urban environmentalists, for example, are rethinking sidewalks and streets in ways that would benefit them.

Now, the outcome of that is certainly a more accessible city, but I think it’s more significant than that. It’s a complete rethinking of the dynamic and the relationship between sidewalks and streets and cities and how we navigate them. So that’s what I mean by a different approach rather than an access-based approach. It still promotes accessibility, of course, but it’s not about accommodations or modifications to what exists. It’s a thorough rethinking of urban space.

I imagine there are some overlaps between disability issues and sustainability, which you partly just alluded to.

Cities probably feel more pressure nowadays to deal with problems in climate change rather than disability. But a lot of the spatial ideas about mitigating problems with “modern cities”—the physical infrastructure of cities and climate change—a lot of those ideas could benefit disabled people.

I’m not sure what is first. City planners are thinking about things like stormwater runoff and the abundance of water in the environment and how it impacts urban spaces and flooding and all these things. But all those issues that deal with urban topography can also involve disability perspectives. It would be very hard for a city that’s trying to rebuild sidewalks and streets to build them in a way that would make them even less accessible than they are currently.

With climate change and Covid-19 and these sorts of massively disruptive issues, do you feel like there’s more openness now to discussions of how we might develop cities and spaces for people with disabilities and others?

Yes, absolutely. One of the things that has been exciting for me is that after publishing this book, The Architecture of Disability, I have had so many institutions, schools, and organisations like PropertyGuru come and talk to me. I think one of the reasons is because after Covid-19 people have had a very intimate experience of disability or impairment in some way. A lot of people felt as if they suddenly had to think about their bodies, breathing, and space in a way that they never had to before—but that’s very familiar for people who have chronic disabilities.

I think it’s brought a sentiment about disability into the public discussion that wasn’t there before. A lot of people became very frightened and realised that their physical environment—the buildings they lived in and worked in—was not necessarily supporting them physically. Or, even worse, they were unhealthy. I think it’s raised all kinds of questions about buildings and health and cities that are important.

What is on the horizon for you in the coming months?

The Walker Art Centre in Minneapolis has asked me to do a project related to The Architecture of Disability. They’ve asked me to rethink about a half-dozen everyday objects with some colleagues of mine. We’ll look at them through the perspectives of disability—but also think about ways we might question what’s “normal” around certain objects. This includes everything from toilets to park benches and these sorts of things. It’s an issue with interesting opportunities for cross-cultural perspectives. A lot of what we’re looking at involves thinking about posture. So, revamping each of these objects through the perspective of disability and through other perspectives as well.

This article was originally published on asiarealestatesummit.com. Write to our editors at [email protected].

Recommended

6 reasons why Bang Na is Bangkok’s hidden gem

This Bangkok enclave flaunts proximity to an international airport, top schools, and an array of real estate investment options

AI transforms Asia’s real estate sector: Enhancing valuation, customer interaction, and sustainability

From property valuation to measuring sustainability, AI is impacting nearly every aspect of Asia’s real estate industry

Bangkok’s luxury real estate flourishes amid economic challenges

New luxury mega projects boost the top end of Bangkok’s market, but stagnancy reigns elsewhere due to weak liquidity and slow economic growth

Investors shift focus to suburban and regional markets as Australian urban housing prices surge

Investors are gravitating to suburban areas and overlooked towns as Australia’s alpha cities see skyrocketing demand and prices